The Persecution of Buddhism in Shikoku

Home » The Persecution of Buddhism in Shikoku

The Persecution of Buddhism in Shikoku

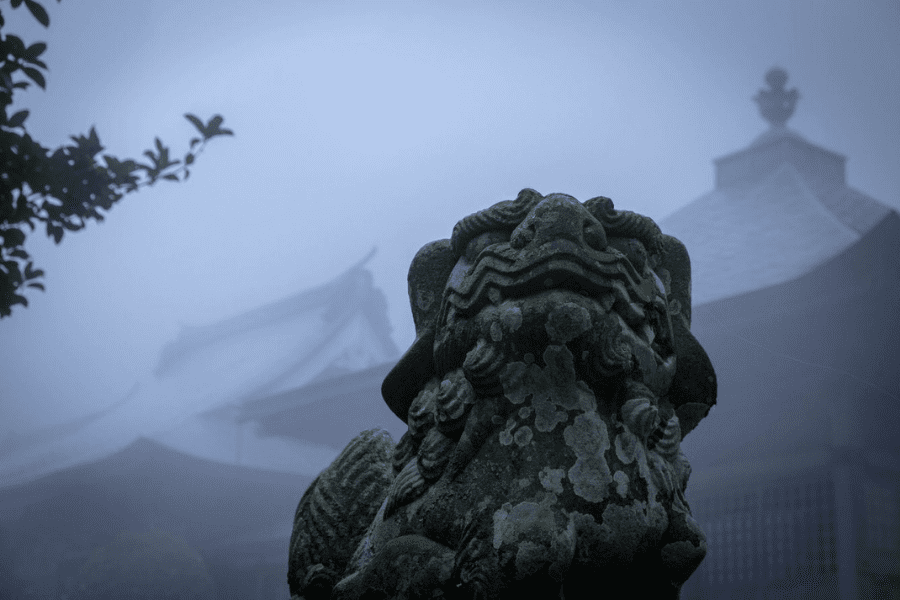

When you visit Shikoku, it won’t be long before you notice that nearly all the stone Buddhas have a neck problem – most have apparently had their heads knocked off. Sometimes the head has been cemented back on. Often the head has been replaced, with infelicitous outcome. So what’s this all about?

The syncretism of Buddhism and Shintō

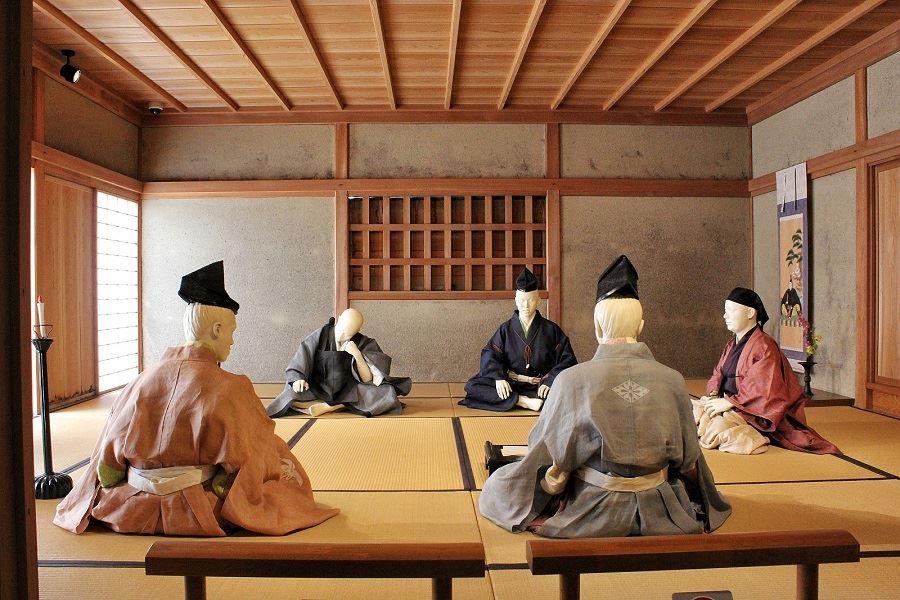

From ancient times, the Japan’s native Shintō religion had been harmonised with the beliefs of Buddhism, which is a foreign religion from India and China. A theory took hold that Buddhist deities appear to the Japanese as living Shintō deities in order to save sentient beings. This put Buddhist monks in a stronger position than Shintō priests, since it was the monks who controlled the ‘essence’ of godhood. Therefore, in the Edo period, it was common for temples linked to the shogunate system to manage shrines as subordinate entities.

Ever since the first Christian missionary had visited Japan in 1549 and made converts, Christianity persisted in Japan, despite persecution by successive Shōguns. During the Edo period, people were obliged to register with a temple to prove that they weren’t Christian, and to contribute to the upkeep of the temple. This system gave temples the power to extort payment from their parishioners under threat of ‘revealing’ them to be secret Christians or heretics, which naturally generated ill will. In addition, temples offered loans to both farmers and samurai at high interest, further cementing their image as parasitic entities.

Official and popular persecution

However, this situation changed completely with the collapse of the shōgunate and the establishment of the Meiji government in 1868. The separation of Shintō and Buddhism, called shinbutsu bunri, was the first policy that the Meiji government undertook when the modern nation was founded, restoring royal government, and establishing the unity of church and state, nationalising Shintō under the authority of the Emperor.

Buddhist monks were denied status as overseers of shrines and were required to return to secular pursuits and give up their rank in the Buddhist hierarchy. Shrines were ordered to conduct detailed investigations of their origins and eliminate all Buddhist elements. The national government had no particular intention of abolishing Buddhism. But the public had other ideas. The anti-Buddhist sentiment of Japanese classical scholars, Confucian scholars, and Shintō priests, and resentment of the domineering and corruption of monks who were once backed by the power of the shōgunate, gradually coalesced into a radical movement aimed at doing away with Buddhism completely. In various places, Buddhist statues and altars were destroyed and burned, temple land was confiscated, and monks were driven out. These actions are collectively called haibutsu kishaku, literally “abolish Buddhism and destroy Buddha”.

The violence of the movement peaked in 1871 and began to subside. The abolition and merger of temples was almost completed by the 8th year of Meiji, and the ministry responsible was disbanded.

Anti-Buddhist action in Shikoku

In Shikoku, the zeal of the popular movement to abolish Buddhism differed in each of the newly established prefectures. Tokushima complied with government decrees, but took no further action. In Ehime, there was some opportunistic confiscation of temple land. However, the responsible authorities in Kōchi were led by a hardliner who pushed for the complete abolition of Buddhism. Even the former feudal lord called for traditional Buddhist funerals to be abandoned in favour of Shintō funerals. In Kagawa, the Tadotsu clan who were friendly with the old Tosa clan, were keen to replace the temples. But when the policy to consolidate all of the temples and sects in the territory was put into effect, it drew determined opposition from all quarters, especially from conservative farmers. There was even talk that priests might commit acts of terrorism against the clan using bamboo bombs, so the government abandoned their plans.

The official government policy and the popular movement against Buddhism took a heavy toll on the Shikoku Pilgrimage. Of the sixteen Shikoku Pilgrimage temples in Tosa, seven temples submitted notices of abandonment, and other temples more or less gave up without notice. A dispute over which temple was No. 30 that arose due to the separation of Shintō and Buddhism was only resolved in 1994.

The separation was most disruptive to the temples around Mt. Ishizuchi, where syncretism had a history going back centuries. Yokomine-ji and Maegami-ji were severely affected. The Shugendō deity they worshipped, Zaō Gongen, was deemed to be Buddhist, and the temples were required to give precedence to the Shintō Ishizuchi Shrine. It took several decades to restore the position of the temples.

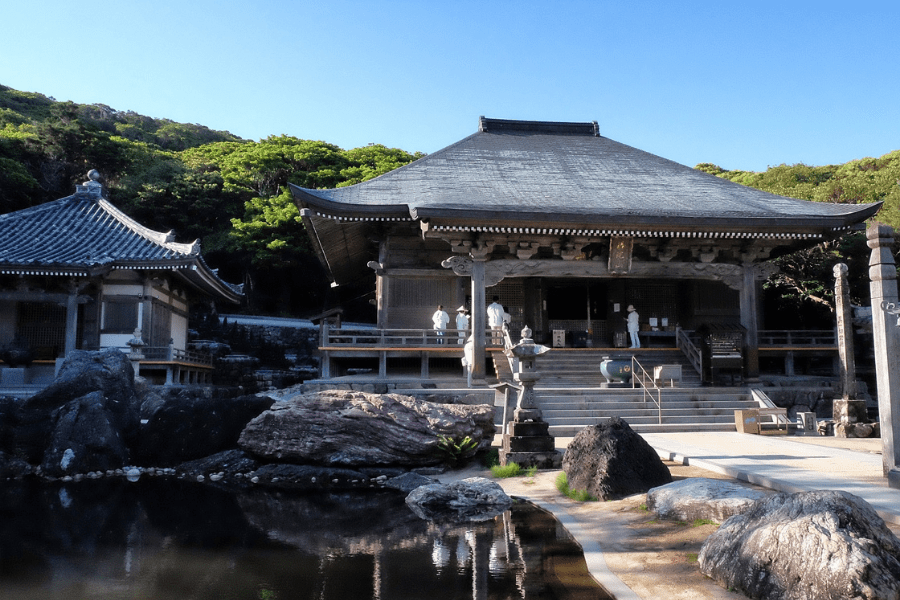

A pilgrim who stayed at Hotsumisaki-ji in 1907 wrote about the scene of utter devastation, with dilapidated temple buildings and accommodation, and monks struggling to rebuild. The description shows that the economic situation of the pilgrimage temples continued to be grim throughout the Meiji period.

Nevertheless, there was a backlash against the new policy. Commoners were unhappy with the disruption of their ancestral funeral practices, including the memorialisation of their dead. In Kōchi, which lost many of its temples, there was a movement to invite temples to relocate from Honshu. The pilgrimage gradually recovered too. By the 25th year of Meiji, an official of Tatsue-ji reported about 500 pilgrims a day between March and May, and in the Taishō period, the number of pilgrims visiting temples had reached nearly a thousand a day.

The Meiji period reaction against Buddhism had an interesting precursor in China about a thousand years earlier, ten years after the death of Kūkai. In 840, Emperor Wuzong of Tang assumed the throne. He was a Daoist who promoted Daoism as the natural religion of the Han Chinese. Wuzong hated Buddhism as a foreign religion and regarded its practitioners as tax evaders. Consequently, he ordered the destruction of some 4,600 monasteries and 40,000 temples, and required the secularisation of around 250,000 Buddhist monks and nuns. This persecution was on a scale far larger than in Japan.

Today, the most prominent evidence of the anti-Buddhism spasm in Shikoku is the cement holding the Buddha’s heads on.

Related Tours

Experience the most beautiful and interesting temples of the Shikoku Pilgrimage in seven days.

A tour for families or friends, staying in the most characterful kominka and ryokan of Shikoku.

Visit the most beautiful and interesting temples of the Shikoku Pilgrimage and walk the toughest trails.