Shikoku Crafts

Home » Shikoku Crafts

Shikoku Crafts

Shikoku is home to a wide variety of attractive traditional crafts. You may encounter some of them on your visit, or you can choose to seek them out, whether to purchase as souvenirs, or to have a go at making them yourself.

Textiles

Iyo-ito raw silk (Ehime)

Name in Japanese: 伊予生糸

Pronunciation: iyo ito

Sericulture started in the early Meiji period in Nomura, where the upland fields fed by rivers flowing from the Shikoku Mountains are good for growing the mulberry required to feed silkworms. This silk gained a reputation both in Japan and abroad for its graceful gloss, soft, fluffy texture, and its unparalleled volume. For decades, raw silk from cocoons raised in an ideal climate and produced using advanced silk-reeling technology was traded under the ‘Camelia’ trademark. This highly profitable business ensured the prosperity of the town. Silk from Nomura was worn by priests at Ise Shrine and by Queen Elisabeth II at her coronation. Since 2015, Iyo Raw Silk from Nomura has been recognised an important regional product.

You can visit various sites in Ehime to discover the beauty and fascination of silk production.

Awa Shō-ai Shijira-ori cotton fabric (Tokushima)

Name in Japanese: 阿波正藍しじら織

Pronunciation: awa shō ai shijira ori

Awa Sho-ai Shijira-ori is a cotton fabric mainly produced in Tokushima city. It’s characterized by its uneven surface and vivid colours achieved with indigo dyeing. The finely wrinkled surface of the fabric makes it pleasant to the touch and breathable, and it doesn’t cling to damp skin.

The fabric originated when a woman named Kaifu Hana invented the technique at the end of the 18th century. When she was hanging out a cotton striped fabric called tataeori, which was popularly made in the Awa region at that time, a sudden shower caused the fabric to get wet and shrink. She took note of the shrinkage and used it to intentionally create an uneven cotton fabric.

In the production process, the fabric is dyed, wrung out, and dried many times to ensure that the indigo colour doesn’t become too dark after a single dyeing process. The unique texture and colour are achieved by washing the fabric 30 times in water. This rinsing is the secret to producing the deep indigo colour known as champagne blue.

You can tour a factory to see the production process, and you can try dyeing various clothing items.

Iyo Kasuri ikat (Ehime)

Name in Japanese: 伊予かすり

Pronunciation: iyo kasuri

Matsuyama’s traditional textile, Iyo Kasuri, is a kind of ikat. Production of Iyo Kasuri began about 200 years ago, when a local woman, Kagitani Kana, devised a method of reproducing a simple woven pattern. This became a hit nationwide so that Iyo Kasuri accounted for 26% of all ikat produced in 1904. It was widely used for kimono and other garments. Today it’s still produced on hand looms.

In Seiyo, you can see the original looms, and in Imabari you can try weaving similar textiles on a hand loom.

Dyeing

Indigo dyeing (all Shikoku)

Name in Japanese: 藍染

Pronunciation: aizomé

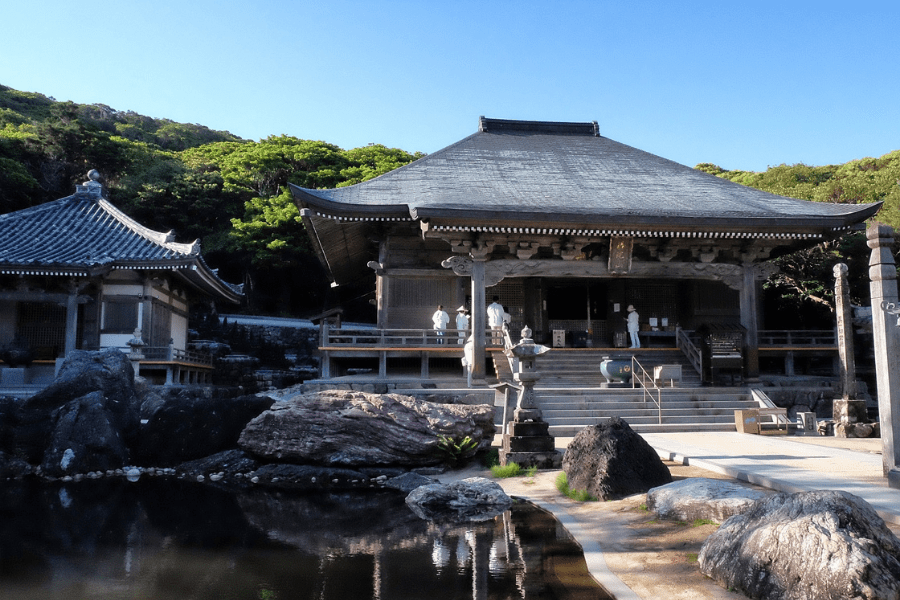

One of the most prominent traditional crafts in Shikoku is indigo dyeing, a once-thriving industry that has its roots in Wakimachi, Tokushima, a small town located on a calm stretch of the Yoshino River which flows into the sea in Tokushima City. Various factors such as the sumptuary laws of the samurai, the regular flooding of the river, and the logistically advantageous siting contributed to the prosperity which the town enjoyed in the Edo and Meiji periods.

At Aizumi in Tokushima Prefecture, there’s a museum where you can learn about the history of indigo, and there are several places where you can see indigo being grown, fermented, and readied for dyeing. In all four prefectures of Shikoku, you can try dyeing various clothing items.

Lost Wax Dyeing (Ehime, Kagawa)

Name in Japanese: ろうけつ染め

Pronunciation: rōketsu zomé

With this method, hot wax is applied to textiles as a resist, and colourful pigments are painted by hand directly onto the fabric. The fabric is washed in hot water, dissolving the wax. This allows for highly precise colouration, whether for small items such as fans and bags, to huge flags, banners, and carp streamers.

In Ehime there are several studios where large banners have been dyed for generations and with a reservation, you can go and watch the artisans at work. In Kagawa, you can try dyeing the fabric covering of an uchiwa fan, which you then apply to the split bamboo frame.

Paper making

Awa Washi (Tokushima)

Name in Japanese: 阿波和紙

Pronunciation: awa washi

Awa Washi is Japanese paper made mainly in Yoshinogawa and Miyoshi in Tokushima Prefecture. Awa washi has a beautiful, raw colour that can only be achieved with handmade paper, and is resistant to tearing even when wet. In addition to the three main raw materials for washi used in other regions, Awa washi is also made from hemp, bamboo, and mulberry.

Awa washi has a long history, with production beginning approximately 1,300 years ago. In 1583, Hachisuka Iemasa, the first lord of the Tokushima Domain, encouraged the protection of paper mulberry and focused on paper manufacturing, which led to its significant development as a local industry.

Recently, many new products have been developed along with the changing times, such as Japanese paper used for interior decoration and for inkjet printing.

Ōzu Washi (Ehime)

Name in Japanese: 大洲和紙

Pronunciation: ōzu washi

Ōzu washi is handmade washi made in the area around Seiyo. Due to its smoothness and resistance to ink bleed, Ozu washi made with a plant called mitsumata is considered the best in Japan for calligraphy. The origin of Ōzu washi is not known for certain, but there are references to its production in books written during the Heian period (794-1185). During the mid-Edo period (1688-1704), papermaking master of the Ōzu clan, Sūshō Zenjōmon introduced the techniques still used today.

After World War II, the demand for washi declined significantly due to the development of machine made paper, but manufacturers continued to produce handmade washi, establishing it as high-end brand paper. Today, Ōzu produces a variety of washi paper products in addition to calligraphy paper.

Tosa Washi (Kōchi)

Name in Japanese: 土佐和紙

Pronunciation: tosa washi

Tosa washi is made mainly in Tosa, Kōchi Prefecture. Tosa washi is characterized by its thinness combined with durability and tear-resistance, and Tosa Tengu Jōshi is the thinnest washi in Japan at 0.03 mm. Thanks to its fineness, it’s used for the restoration of cultural assets.

The history of Tosa washi is not clear, but washi was already being made in the Heian period (794-1185). Later, during the Edo period (1603-1867), the paper industry flourished under the protection of the Tosa clan, and washi paper in seven colours was presented to the shōgunate as a special product of the Tosa domain.

Tosa washi is used for everything from restoring cultural assets to familiar items such as wrapping paper for confectionery.

There are facilities in each prefecture where you can try making various styles of washi paper.

Iyo Mizuhiki (Ehime)

Name in Japanese: 伊予水引

Pronunciation: iyo mizuhiki

Mizuhiki is a string-like material made of Japanese paper, thinly cut and twisted, glued, dried, and hardened. It can be used in this state, but it’s also often wrapped with thin gold or silver paper, or with ultra-fine fibres. The colourful strings are used as a decorative binding for items of high value such as envelopes containing gifts of money, and highly priced boxed meals. The paper string can also be woven to create surprisingly life-like sculptures and sophisticated art objects.

Iyo Mizuhiki was invented as a robust but disposable string for tying hair in a topknot in the Edo period. But a decree of the Meiji period calling for the end to this hairstyle made the string redundant. However, in Ehime, the paper string was quickly repurposed as a decorative binding for the envelopes of money that soldiers going to war gave to their families. This paper was made in what is today Shikokuchūō, which stands near mountains where the raw materials for paper grow, and water flows abundantly.

In Shikokuchūō, you can visit studios where Mizuhiki is used in a variety of innovative applications.

Ceramics

Ōtani Ware (Tokushima)

Name in Japanese: 大谷焼

Pronunciation: ōtani yaki

Ōtani ware is a ceramic produced in Naruto, Tokushima Prefecture. It’s known for its rough, rustic clay texture and slightly shiny lustre from the iron in the clay, and also the huge vats suitable for use as tanks for holding indigo dye. These are made on a potter’s wheel powered by a man lying on his side to turn the wheel, while another man moulds the vessel. Products large and small are fired in climbing kilns which are the largest in Japan.

Ōtani ware is said to have originated in the late Edo period when Bun’emon, a craftsman from Bungō Province (present-day Oita Prefecture), visited Ōtani village and demonstrated how to make pottery using a potter’s wheel. The 11th lord of the domain, Hachisuka Haruaki, was so interested in this that he invited many craftsmen from Kyushu to start manufacturing pottery, but the business was discontinued after only three years due to economic difficulties. Later, an indigo merchant, Kaya Bungorō, invited craftsmen from Shigaraki in Shiga, had his younger brother learn the techniques, and built a climbing kiln, reviving Ōtani ware.

Today, craftsmen still create each piece individually with a potter’s wheel, so each item is unique. In addition to large ceramics, the potters also manufacture everyday tableware.

Tobe ware (Ehime)

Name in Japanese: 砥部焼

Pronunciation: tobé yaki

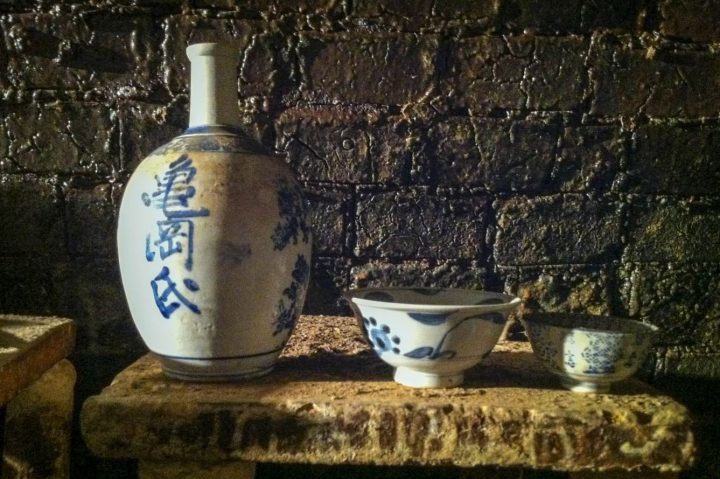

Tobe ware is a ceramic made in the town of Tobe, Ehime Prefecture. Tobe ware is characterized by indigo designs hand-applied by craftsmen to white porcelain. The pottery is durable and heavy, and is not easily broken or chipped, making it ideal for daily use.

Tobe ware originated in the mid-Edo period when Katō Yasutoki, lord of the Ōzu domain, began developing porcelain as a measure to overcome the domain’s financial difficulties. The Ōzu Clan, which originally specialized in a type of whetstone called Iyoto, sought to reduce costs by using the waste stone produced in the manufacture of Iyoto as a raw material for porcelain. In the Meiji period (1868-1912), mass production became possible, and porcelain was exported domestically and abroad. Later, the pottery declined temporarily due to a recession, but the folk art movement led by Yanagi Muneyoshi led to a revaluation of handmade pottery and the revival of Tobe as a production centre for handmade, hand-painted ceramics.

Due to its robustness, Tobe ware is used widely in restaurants in Shikoku. Recently, many young people have moved to Tobe and started producing new designs. In Tobe, there’s an excellent museum and you can visit many of the pottery studios. There are also numerous facilities where you can try painting a premade item.

Lacquer

Kagawa Lacquer Ware (Kagawa)

Name in Japanese: 香川漆器

Pronunciation: kagawa shikki

Kagawa lacquerware developed in the city of Takamatsu, Kagawa Prefecture. It includes a wide range of products such as bowls, trays, cups, and lunchboxes. A variety of techniques that were developed independently are used, all of which develop a lustrous sheen and sophisticated patina as they’re used.

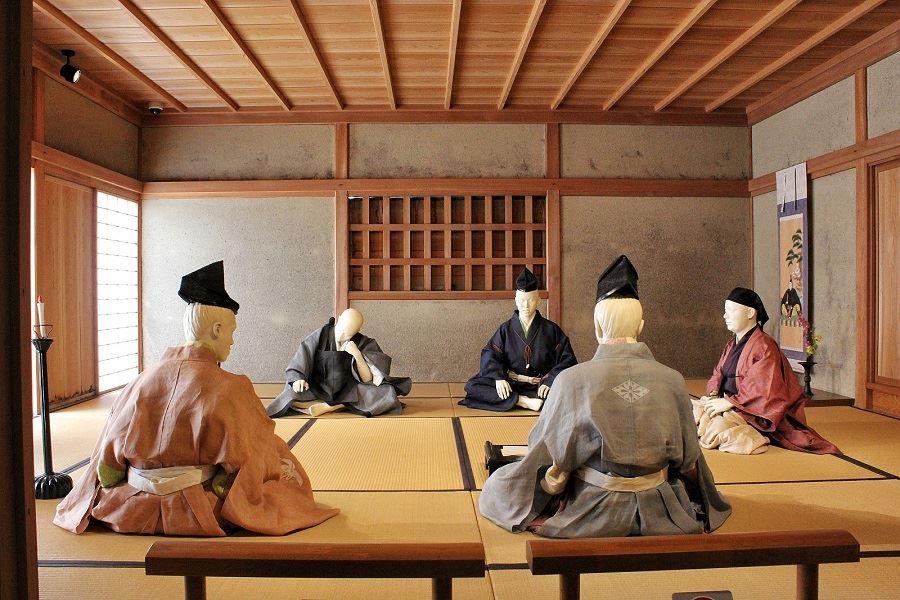

Kagawa lacquerware developed under the protection of the Matsudaira clan, the first lords of the Takamatsu domain, during the Edo period (1603-1868). Matsudaira Yorishige, the first lord of the Takamatsu Domain, encouraged the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, and haikai in order to develop culture and the arts, and trained many master craftsmen and masters. One of them, Tamakaji Zōkoku studied lacquerware techniques from China and Thailand and developed them into his own techniques.

Many people think of lacquerware as black or vermilion coloured vessels used for celebrations and other special occasions. However, Kagawa lacquerware is available in a wide variety of colours and many modern designs perfect for everyday use. In Takamatsu, you can try lacquering chopsticks, bowls, and fridge magnets. You can also try carving an item that’s been lacquered with several layers of different colours, revealing the colours depending on the depth of each cut.

Fans

Marugame Uchiwa (Kagawa)

Name in Japanese: 丸亀うちわ

Pronunciation: marugamé uchiwa

Marugame Uchiwa is a type of fan, made by hand in the city of Marugame, Kagawa Prefecture. One hundred million fans are made each year, and Marugame accounts for 90% of the domestic market share. The handle and spokes of Marugame fans are made from a single piece of bamboo, making it light and strong.

The first Marugame Uchiwa was invented in the early Edo period (1603-1867) as a souvenir for the Konpira Festival in Shikoku. It was vermilion red with the seal of Konpira Shrine in gold. Later, making fans was encouraged as a domestic occupation for the lower-ranking samurai of the Marugame domain, and it rapidly developed into a local industry.

Although demand temporarily declined due to the spread of electrical appliances such as air conditioners, uchiwa fans are now used not only for keeping cool, but also for various purposes such as cooking, sun protection, fashion, and decoration. Marugame has responded to these changes in demand by developing many products with shapes and designs to suit different uses.

At various places in Kagawa, you can try making your own original fan, including dyeing the fabric covering using the lost wax technique.

Blacksmithing

Tosa Uchihamono (Kōchi)

Name in Japanese: 土佐打刃物

Pronunciation: tosa uchi hamono

Tosa Uchihamono is hand-forged cutlery made in and around the city of Kōchi in Kōchi Prefecture. Also known as “Tosa free forging”, the shape and weight of each item can be adjusted according to the intended use and the user’s preference.

Besides the production of swords, Tosa blacksmiths produced cutting tools for forestry and agriculture, Kōchi’s main industries. The full-scale development of Tosa blacksmithing began in 1621 when the Tosa clan’s Genna Reforms led to the development of new rice paddies and the use of forest resources, increasing the demand for blades. Both the quantity and quality of production greatly increased.

Since craftsmen make each product individually, a wide variety of products can be manufactured in small quantities with high quality. Besides shopping for nice knives, you can try making your own knife from scratch with a friendly blacksmith beside the Shimanto River.

Basketry

Iyo Bamboo Craft (Ehime)

Name in Japanese: 伊予竹工芸品

Pronunciation: iyo take kōgei hin

Iyo bamboo craft is a type of basketry practised in Matsuyama using high-quality green bamboo from Ehime Prefecture and tiger bamboo from Kōchi Prefecture. The bamboo is dyed twice, in red and black, achieving a rich, sophisticated patina that only improves with age. The bamboo is woven freestyle without using a mould to create patterns that vary from open to closely knit, sometimes in the same item. Although traditional designs are still produced, the craftsmen of Matsuyama are adapting their techniques to modern applications, such as interior décor with speakers and lights.

You can try making a simple item under the guidance of an expert craftsman.

Vine weaving (Tokushima)

Name in Japanese: かずら細工

Pronunciation: kazura saiku

The vine bridges in Iya Valley in Tokushima are known as one of Shikoku’s most iconic sights, but few people know that the vines called kazura used to make the bridges have also traditionally been the material for much smaller objects such as baskets. These vines grow wild in the mountains around Mt. Tsurugi, and nature was thoughtful enough to produce several varieties of varying thickness suitable for many different applications. Going into the mountains to find the vines is a labour of love.

Today, kazura saiku tends to be used for interior décor rather than practical items. In Iya, and Mugi on the coast, you can try making objects with these flexible vines.

Dolls

Hime Daruma Dolls (Ehime)

Name in Japanese: 姫だるま

Pronunciation: himé daruma

Hime Daruma dolls are a traditional craft of Matsuyama. They’re round with a weight in the bottom, so they always return to the upright. Children who play with Hime Daruma dolls are said to grow up healthy. They also make popular wedding and childbirth gifts. Male versions of this kind of doll are common throughout Japan and they’re known as daruma after Bodhidharma, the founder of Zen Buddhism. But female versions are unusual, and they’re essentially unique to Matsuyama. Hime, which means ‘princess’, refers to the legendary Empress Jingū Kogō, who is said to have visited Dōgo on the way to a conquest of Korea. The original dolls were made of wood, but today’s dolls come in two main variants, papier-mâché and brocade.

The papier-mâché type are generally painted bright red like conventional daruma dolls, while their faces are made of white bisque ceramic, painted by hand with red lips and black eyes. Their hair may be painted, or they may have artificial hair. The papier-mâché type typically comes unchaperoned. These are often given to pregnant women as talismans for an easy birth and quick recovery.

The brocade variety on the other hand, come as a couple representing the Empress Jingū and her husband Chūai. She wears red brocade, while he wears blue, or gold. These are frequently given as wedding presents.

The dolls are light and easily transported, so they make good souvenirs. They also come in a range of sizes. Besides the dolls themselves, you can find Hime Daruma used as a cute motif on mobile phone accessories, purses, handkerchiefs, and other textile items. You can try making your own, an activity that takes about an hour.

Embroidery

Temari (Kagawa)

Name in Japanese: 手まり

Pronunciation: temari

Temari are balls embroidered with an endless variety of elaborate and exquisite patterns, created from simple and mundane materials – rice husks, paper, and cotton thread. A few handfuls of rice husks are wrapped with thin tissue paper. This is wound repeatedly with cotton thread of a single colour, resulting in a perfectly spherical ball. On this base, cotton of different colours is used to create patterns, which are built up one thread at a time. The threads are driven through the ball with a needle. Since the threads are stretched from point to point, the patterns are necessarily made of straight lines, but by subtly arranging the lines at angles to each other over the surface of the ball, a skilled practitioner can create the illusion of curves.

Temari were once made all over Japan. Originally, they were crafted for the daughters of feudal lords by their handmaidens using brightly coloured silk thread. The balls were also used for the aristocratic game of kemari, where the players stand in a circle and kick the ball, attempting to keep it constantly in the air. However, when cotton thread became available to commoners, temari became widely popular, especially in Kagawa where cotton was grown. But with the replacement of old-school crafts by digital entertainment, temari nearly disappeared.

Influenced by her father-in-law who conserved traditional crafts, Araki Eiko began workshops to pass the skills down to new generations. Today, she runs an attractive studio where you can try embroidering a small temari ball yourself.

Wax

Wax candles (Ehime)

Name in Japanese: 和蠟燭

Pronunciation: warōsoku

The town of Uchiko, Ehime, grew wealthy from the Edo period with the production of natural wax from the haze tree, and various wax products, especially candles. The Ōmori family have been making wax candles for six generations, and today, two generations of the family continue the tradition at their shop in the street of traditional buildings in the town.

The process involves heating natural wax over a charcoal fire to 45°C. Bamboo sticks are wrapped with washi paper and rush to form the wick, with floss silk to hold them together. Hot wax is then scooped by hand and rubbed up and down the wick repeatedly, gradually increasing the thickness of the candle. Finally, the candle is polished smooth by hand, leaving a natural touch like wood. When the candle is cut to the standard length, you can see rings like the trunk of a tree where the layers of wax were applied and cooled.

Uchiko wax candles have a very tall, stable flame that produces no soot. The natural wax also has no smell as the candle burns. Nor does the wax drip. These characteristics amazed visitors to the Paris Expo in 1900 where the candles were exhibited.

You can watch the craftsmen at work, and they answer all sorts of questions with good grace. In the same street where they have their shop is a fascinating museum of wax production in the former home a wealthy wax merchant.

Miscellaneous

Gilding (Ehime)

Name in Japanese: ギルディング

Pronunciation: girudingu

At Ikazaki in Ehime, Saitō Hiroyuki makes washi paper by hand and then applies gold leaf to it in elaborate and beautiful designs. Although gilding is also an Asian art, Saitō-san took his inspiration from European gilding. The company, Ikazaki Shachū, places a strong emphasis on regional contribution through profit from high value added products, and it was inspired by Sakamoto Ryōma, hero of the Meiji Restoration, who sought to strengthen and enrich Japan through trade.

At the company’s busy and atmospheric headquarters in Ikazaki, you can watch the craftspeople at work and try gilding a piece of washi paper, which makes an attractive souvenir.

Inkstones (Kōchi)

Name in Japanese: 土佐硯

Pronunciation: tosa tsuzuri

Ink used for calligraphy with a brush came to Japan from China, and along with it came the inkstone, an essential tool for abrading an inkstick and wetting the powder created. Today, inkstones are only used by calligraphers, but the demand is sufficient to support inkstone factories here and there in Japan, especially in areas with good slate formations. One of these is in Mihara, Kōchi.

Here, slate is taken from the hill behind the factory and is crafted into inkstones that vary from the simple and functional to the very ornate. The craftsmanship that goes into sanding the slate requires a high degree of precision.

At Mihara, you can make an inkstone or any other item of your choice using slate, under the guidance of an English-speaking expert craftsman.

Wagasa umbrellas (Tokushima)

Name in Japanese: 和傘

Pronunciation: wagasa

The wagasa or Japanese paper umbrella is a complex object. It requires skills in bamboo crafting, lacquering, paper making, dyeing, and processing, and weaving. The oiled washi paper of the umbrella offers protection against both rain and sun.

Around 1945, more than 200 households were involved in wagasa production in the Mima area, and at its peak, nearly 900,000 wagasa umbrellas were produced annually. In recent years, only two houses have been making wagasa using traditional methods, but in an attempt to revive the Mima wagasa industry, a group of volunteer citizens set up the Mima Wagasa Production Group and works hard every day to produce wagasa.

The group assembles the bamboo used to make the umbrella bones, dyes and oils the Japanese paper, decorates it and applies lacquer to the bamboo. To finish the umbrella, cotton threads of different colours are elaborately arranged under the canopy. The umbrellas are produced and sold at the Mima City Traditional Crafts Experience Centre in Wakimachi. Here you can watch the craftspeople at work, and try your skills at making miniature umbrella ornaments.

Wood carving (Kagawa)

Name in Japanese: 菓子木型

Pronunciation: kashi kigata

Wood carving in Kagawa takes many forms – free standing art objects, panels and screens that divide rooms in traditional buildings, carved and painted bamboo, and the moulds used for making sugar sweets. Although all of these arts require a high degree of precision, the latter are particularly impressive since they’re carved in the negative so as to produce highly detailed pressed products.

You can see these refined artworks in souvenir and antique shops all over Kagawa. But to enjoy the carved moulds at first hand, you should visit one of the workshops where you can make wasanbon sugar sweets. These workshops generally have an extensive collection of large and small hand-carved moulds.

Bonsai (Ehime, Takamatsu)

Name in Japanese: 盆栽

Pronunciation: bonsai

Bonsai is the art of growing stunted but naturalistic trees in containers. The art is practised all over Japan, but afficionados come from around the world to make and purchase bonsai in Shikoku. In Saijō, Ehime, the red pines taken from a small area in the foothills of Mt. Ishizuchi are prized. Several nurseries nurture these precious saplings into works of art that fetch surprising sums. Kinashi in Kagawa is also known as an area that’s ideal for growing the trees that will become bonsai. In both areas, you can visit plantations of pines and many other varieties, and stroll in yards filled with the most remarkable creations, many of which are older than you. Kindly craftsmen will also show you how to make and care for one of these works of living art.

Related Tours

Experience the most beautiful and interesting temples of the Shikoku Pilgrimage in seven days.

A tour for families or friends, staying in the most characterful kominka and ryokan of Shikoku.

Visit the most beautiful and interesting temples of the Shikoku Pilgrimage and walk the toughest trails.